Reels Ads Demystified - Everything You Need to Know in One Infographic

Adshine.pro04/22/2025194 views

Adshine.pro04/22/2025194 viewsLooking for ways to boost your Facebook and IG ads performance?

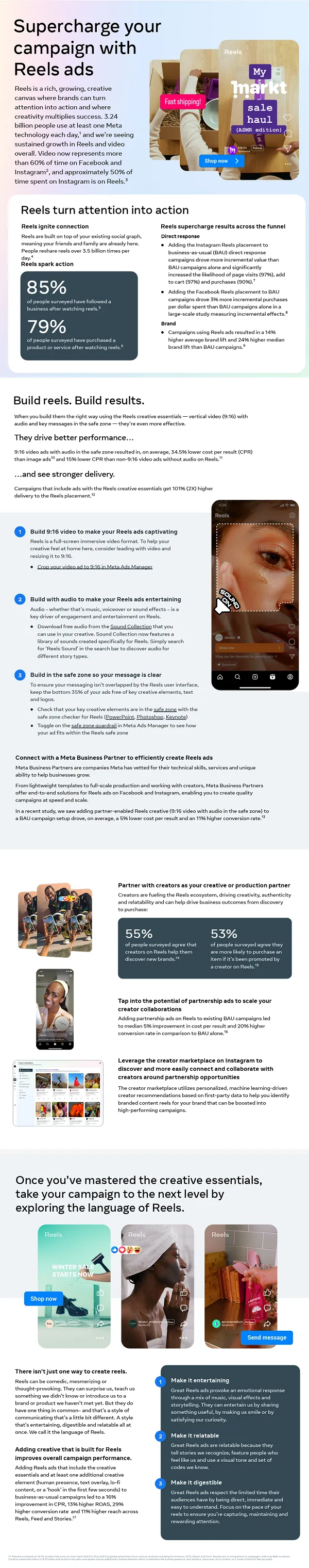

Reels ads could be a good option, with Reels views increasing across both apps, and becoming a bigger part of the broader content experience on both.

Indeed, late last year, Meta reported that users now share 3.5 billion Reels daily across Facebook and Instagram, while 50% of all time spent on Instagram is now dedicated to Reels.

Tapping into short-form video could be a valuable complement for your marketing efforts, and if you are looking to get into Reels promotions, these tips could help.

Meta’s published a short Reels ads guide to provide key tips on how to create more standout Reels promotions. We’ve extrapolated the guide into the below infographic for easier consumption, providing a solid overview of Reels ads essentials.

Worth considering. You can download Meta’s full Reels ads guide (which includes full data references and links) here.

📢 If you're interested in Facebook-related solutions, don't hesitate to connect with us!

🔹 Telegram

🔹Facebook

💬 We're always ready to assist you!